Thinking fast and slow about SRM

Psychologists have shown that we often react first and think second. What shapes our initial reactions to Solar Radiation Management (SRM) and how can we update them?

Humans are not naturally neutral and objective truth seekers. We're capable of complex, rational thought, but it seems this capability evolved to solve problems and persuade others, rather than to pursue the truth.

How will our tendency towards reactive and motivated reasoning play out when it comes to thinking about Solar Radiation Management?

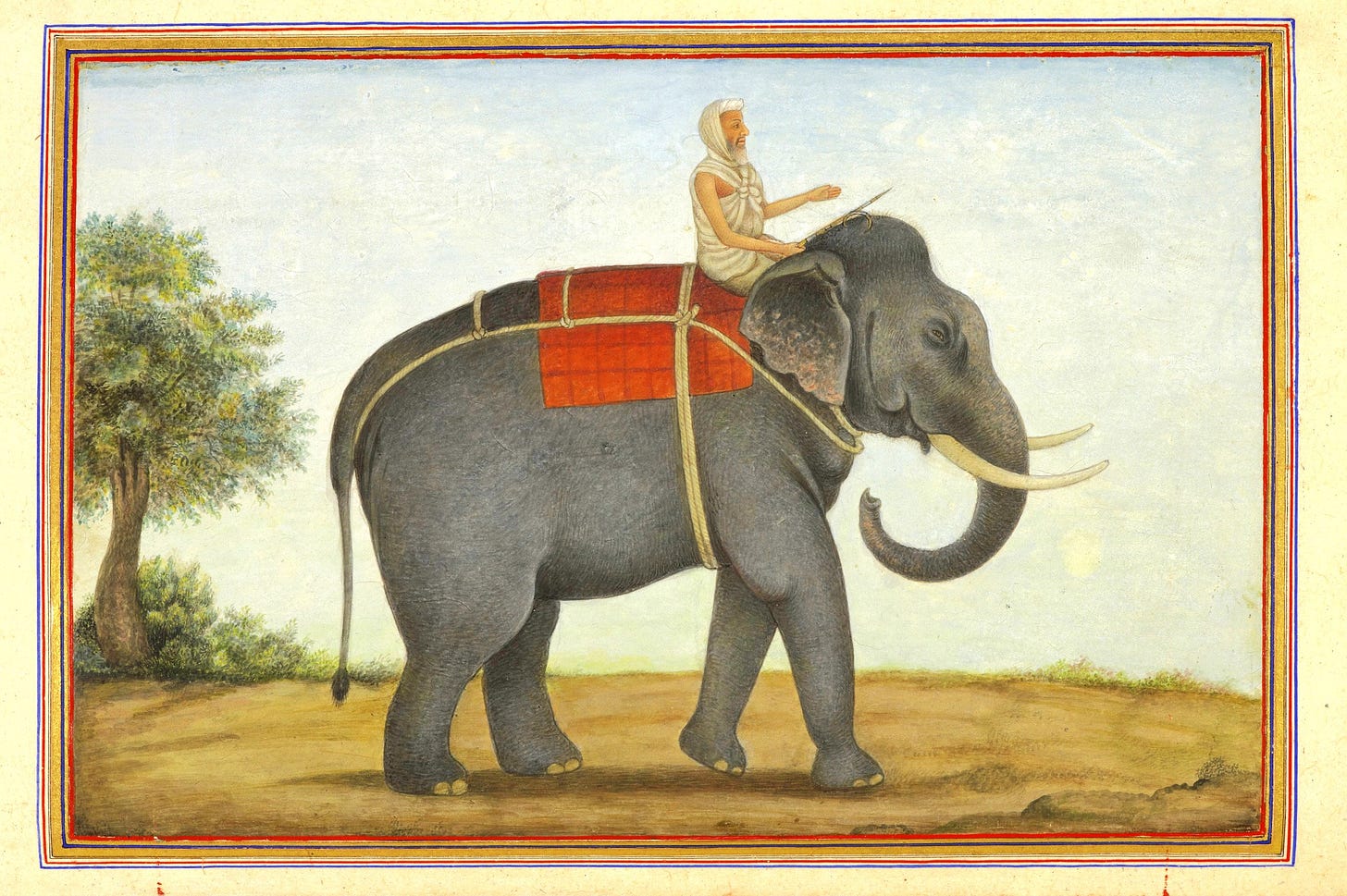

The rider and the elephant

Jonathan haidt, a psychologist of morality and political thought, uses the analogy of the elephant and the rider in his book “The righteous mind”. The elephant is our emotional, instinctive nature and the rider is our conscious, rational mind. This mirrors the two distinct modes of thinking that Daniel kahnemann observed in his research, and popularised in his book: "Thinking, fast and slow."

In haidt's analogy, the rider can influence and guide the elephant, but as the elephant is so much more powerful it ultimately decides where the two are going (Figure 1).

Figure 1. An elephant and its rider (source).

Countless psychological tests, detailed in haidts and kahneman's books have shown that we form an instant judgement about something based on our emotional reactions to it, and some simple rules of thumb, e.g., "natural things are safer than artificial ones". When asked, we can often give good reasons that support our judgement, but research shows that these reasons don't lead to the judgment, instead they are rationalizations for the judgment that we create after the fact.

We can and do change our minds after reflection, letting go of our initial judgments. However, this isnt always the case. Our rational mind - the rider - is often not in the driving seat, but rather it is taken along for the ride as our intuitions - the elephant - charges off. This leaves the rider playing catch up, working to make the best possible case for the actions of the elephant, like a lawyer defending their client.

While we might persuade ourselves and others we always act rationally and with the best of intentions, we shouldn't be so sure. As Benjamin Franklin put it:

"So convenient a thing it is to be a reasonable creature, since it enables one to find or make a reason for every thing one has a mind to do."

The scientific method

Franklin was not only a founding father of the USA and noted wit, but also a pioneering, early scientist. He was fascinated by the natural world and wanted to understand it, but he recognised that his senses and judgments were imperfect guides.

Figure 2. Illustration of Benjamin Franklin’s famous experiment on lightning (source).

The scientific method allows us to overcome these limitations. Scientists start by assuming they are ignorant, make mistakes, and have bad ideas, and only then go to work. We form an idea for how something might be (a hypothesis), come up with a test for it, and then think carefully about whether we've missed something. If we discover something interesting, we then write all the details down and encourage others to reproduce, or falsify, our findings.

While the scientific method is not equally applicable to all areas of research, this self-critical attitude and the peer review of each others' writings is fundamental to most academic work.

By recognising the full extent of our ignorance and systematically attacking it, the scientific method has allowed generations of scientists to identify the truths of our physical world. Over time, these truths have been connected and ramified into the vast network of knowledge that supports and maintains our modern world.

Thinking fast and slow about SRM

If you are at all concerned about our impacts on the environment or worried about the possible dangers of technological development, then I’m certain that when you first heard of SRM, alarm bells started ringing. In haidt's terms, your elephant trumpeted and charged off with your rider taken along for the ride. SRM, and Stratospheric Aerosol Injection (SAI) in particular, produces a whole host of associations that are troubling and which run counter to the rules of thumb that many use to guide their thinking on environmental and technological issues.

While our gut instincts are often right — they've been honed by evolution and experience, after all — they are not always the best guide. Immunizations, for example, run counter to our basic protective instincts — a stranger (painfully) injects a mysterious substance into us or our child — but we overcome this by recognising the protections they offer against a far greater threat.

So it may be with SRM. I'll list some of the instinctive objections that our elephants might raise, and then try to get our riders back in control by questioning them. I won't answer them fully here, but hopefully you'll agree that robust research should be a better guide on these issues than our gut instincts.

"This is unnatural and messing with nature is dangerous" - but, is it more or less dangerous than the impacts of climate change? Would we be messing with nature less if we could use this to limit global warming?

"They're planning to spray sulphuric acid in the sky!? That's so dangerous!" - it would add to acid rain, but we already emit millions of tons of sulphuric acid and this would require a lot less. Wouldn't that be less dangerous than what we're already doing?

"The sky would be whiter? It'll look like blade runner or some other dystopian movie, how horrible!" - the 1991 Pinatubo eruption added more particles to the stratosphere than we'd need for this. Did the sky in 1992 look that dystopian?

"What if they cooled too much? Isn't that what happened in the movie showpiercer? Another dystopia!" - the particles don't last that long, and couldn't we check how much cooling we get and adjust as we go?

Guiding our elephants

Most, if not all, researchers exploring this idea had the same kind of initial reaction to it. Many, including myself, worked hard to try to find the deal-breaking problems that we thought would rule it out1.

The reason that I and others have come round to think SRM might have the potential to really help us, is that we questioned our initial judgments, and looked for evidence to test them.

We might be wrong. This might help or it could prove to be a bad idea. However, the only reliable way to find out is to question our gut reactions, trust in the scientific method, and follow where the evidence leads us. Our rational rider might not always be in control, but it can help point our reactive elephant in the right direction.

FIN

The regional changes in water availability under SAI are the biggest concern, but given that only a minority of places would see greater change, I don't consider this a deal-breaker.

The elephant and rider analogy is appropriate. It’s so important to gather information before acting. But acting when the conditions demand it is necessary. Thank you.